|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

For a number of years after 1918 the First World War was called 'The Great War' in English, and 'Der Große Krieg' in German - simply because it was the great war.

The had been no other war like it, and no one contemplated another war so devastating or so terrible.

It was the 'War to end all wars'.

But, of course, it was not, and 'part two' was to follow about twenty years later.

The great war had a far greater impact on English families than the wars against Napoleon, or the numerous imperial wars of the Victorian era.

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

The first world war was the first war to touch almost everyone in England since the brutal civil wars of the seventeenth century.

|

| Zeppelin Raid |

|

| Gotha Bomber Raid |

It was, without a doubt, the 'Great War', - and the numerous war memorials scattered all up and down the land were mute and tragic testimony to that fact.

And, although the war was fought on the continent, it was surprisingly near.

On the east coast of England the windows and the crockery would rattle during the fierce bombardments on the Somme, and when the devastating British mines exploded, the sound could be heard even in central London.

And then there were the Zeppelin Raids ('Baby Killers') and the Gotha Bomber raids.

The Gotha G.V was a heavy bomber used by the Luftstreitkräfte (Imperial German Air Service) during World War I. Designed for long-range service, the G V series was used principally as night bombers.

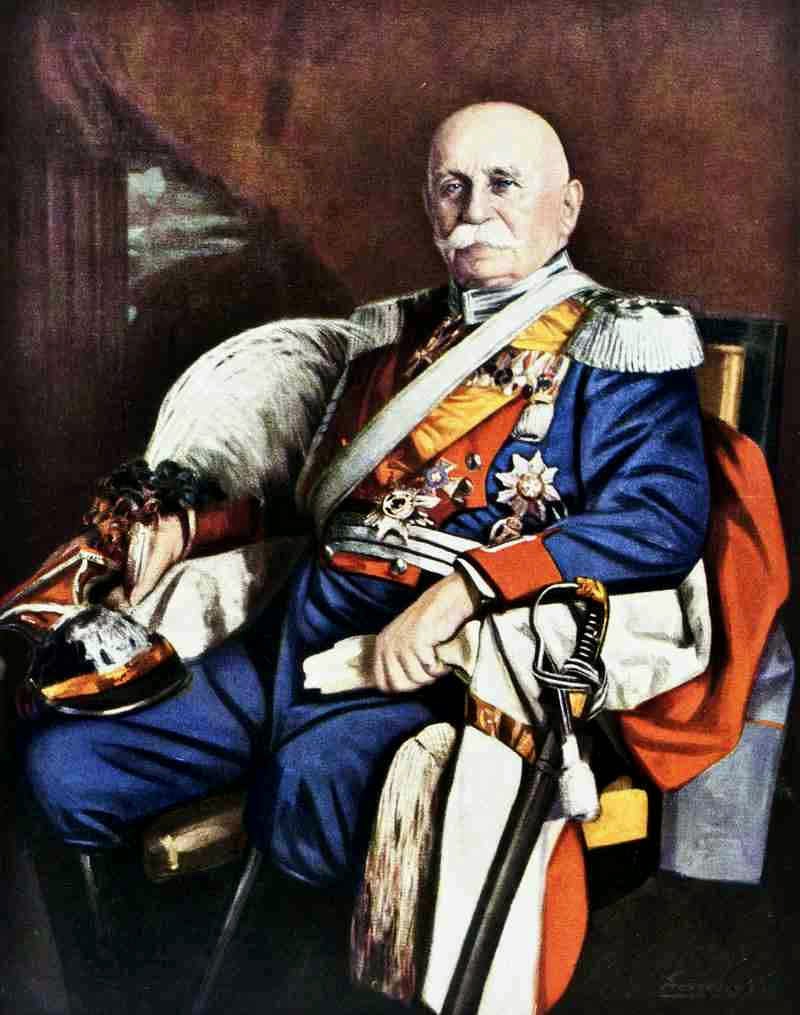

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin (8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) a German general and later aircraft manufacturer, who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's ideas were first formulated in 1874 and developed in detail in 1893. They were patented in Germany in 1895. After the outstanding success of the Zeppelin design, the word zeppelin came to be commonly used to refer to all rigid airships. Zeppelins were first flown commercially in 1910 by Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-AG (DELAG), the world's first airline in revenue service. During World War I the German military made extensive use of Zeppelins as bombers and scouts, killing over 500 people in bombing raids in Britain.

The Gotha G.V was a heavy bomber used by the Luftstreitkräfte (Imperial German Air Service) during World War I. Designed for long-range service, the G V series was used principally as night bombers.

|

| Ferdinand Graf von Zepplin |

The great war, with its coastal bombardments and air-aids was truly a 'people's war'.

But to begin at the beginning - and a very muddled beginning its was ......

The First of August

1914

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

This declaration of war was related to the Schlieffen Plan.

The Schlieffen Plan was a 1905 German General Staff 'thought-experiment', which later became a deployment-plan, and set of recommendations for German Commanders to implement as they saw fit using their own initiative.

The German army would be deployed on the German-Belgian border so it could launch an offensive into France through the southern Dutch province of Maastricht, Belgium, and Luxembourg.

|

| Alfred Graf von Schlieffen |

|

| Helmuth von Moltke |

Moltke also became convinced that Italy would not join in, due to the increasing Italian-Habsburg enmity and the anticipation of British entry into a Franco-German war, in which the Italian economy would be highly vulnerable to blockade.

Under Moltke Aufmarsch I was retired, but in 1914 he attempted to apply the offensive strategy of Aufmarsch I West to the deployment plan Aufmarsch II West.

This plan was designed for a two-front war and so reduced the forces available in the west by a fifth, meaning that the German offensive was too weak to succeed.

Aufmarsch I Ost anticipated war between the Franco-Russian Entente and Germany, with Austria-Hungary supporting Germany and Britain perhaps joining the Entente.

This is near enough what actually happened.

60% of the German army would deploy in the west and 40% in east.

France and Russia would attack simultaneously, because they had the larger force, and Germany would execute an "active defence", in at least the first operation/campaign of the war.

German forces would mass against the Russian invasion force, and defeat it in a counter-offensive, while conducting a conventional defence against the French force, but rather than pursue the retreating Russian force over the border, 50% of the German force in east (about 20% of the German army) would be transferred to the west, for a counter-offensive against the French attack force.

|

| Krasnoye Selo |

On 25 July 1914, the council of ministers was held in Krasnoye Selo at which Tsar Nicholas II decided to intervene in the Austro-Serbian conflict, (which had arisen as a result of the assassination of Erzherzog Franz Ferdinand) and bring the matter a step closer toward a general European war.

He put the Russian army on "alert" on 25 July.

Although this was not mobilisation, it threatened the German and Austrian borders and looked , to all intents and purposes, like a military declaration of war.

On 29 July 1914, Nicholas II sent a telegram to Wilhelm II (The 'Willy-Nicky Correspondence'), with the suggestion to submit the Austro-Serbian problem to the Hague Conference (in Hague tribunal).

Nicholas desired that Russia's mobilisation be only against the Austrian border, in the hopes of preventing war with the German Empire.

|

| Kingdom of Serbia © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

|

| Kaiser Wilhelm II and Tsar Nicholas II |

Nicholas wanted neither to abandon Serbia to the ultimatum of Austria-Hungary, nor to provoke a general war.

In a series of letters exchanged with Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany (the so-called "Willy and Nicky correspondence") the two proclaimed their desire for peace, and each attempted to get the other to back down.

|

| Imperial Russian Troops Mobilise |

Wilhelm II did not address the question of the Hague Conference in his subsequent reply.

Count Witte told the French Ambassador Paleologue that from Russia's point of view the war was madness, Slav solidarity was simply nonsense and Russia could hope for nothing from the war.

|

| Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte |

On 28 July, Austria formally declared war against Serbia, which eventually brought Germany into conflict with Russia and with France and Britain as Russia's allies.

Meanwhile, the Tsar's armies had no contingency plans for a partial mobilisation, and on 31 July 1914 Nicholas took the fateful step of confirming the order for general mobilisation, despite being strongly counselled against it.

|

| Sergei Sazonov |

Germany then replied that Russia must demobilise within the next twelve hours.

In Saint Petersburg, at 7pm, with the ultimatum to Russia expired, the German ambassador to Russia met with the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov, asked three times if Russia would reconsider, and then with shaking hands, delivered the note accepting Russia's war challenge, and declaring war.

So why did Germany declare war ?

Well, as we have seen, Germany deeply feared a war on two fronts - East and West - Russia and France.

And Germany felt encircled - by Russia, France, and England.

Germany also felt obliged to support it's fellow (German speaking) state, Austria-Hungary - although Germany had no real quarrel with Serbia.

However, Germany, like Austria, and the Ottoman Empire, was nervous of Serbian (Slavic) ambitions in the Balkans - and feared the possibility of a Russian attack on Constantinople, and attacks on the Austro-German sphere of influence in the Balkans.

The main cause of the declaration of war by Germany, however, was Russia's unwieldly and unfocussed mobilisation which, while supposedly initiated to support Serbia, appeared to threaten not only Austria, but also Germany - and if Germany was attacked by Russia, then it could also expect to be attacked by Russia's ally - and Germany's old enemy, France.

The German declaration of war was therefore seen by the Central Powers as an act of self-defence.

And what was happening in London ?

Well Asquith had driven to Buckingham Palace early in the morning.

His intention, once he had got the King out of bed, was to ask the monarch to write to the Tsar, asking him to stop the mobilisation of the Russian forces.

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

And why should George, still wearing his brown dressing gown, do this ?

Well, - Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, was George's first cousin (their mothers were sisters).

The letter itself had been written by Edward Grey, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, but it required the King's approval, and his handwritten prefix - 'Dear Nicky'.

Did it do any good ? .... No !

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, KG, KC, PC, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) served as the Liberal Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. As Prime Minister, he led his Liberal party to a series of domestic reforms, including social insurance and the reduction of the power of the House of Lords. He led the nation into the First World War, but a series of military and political crises led to his replacement in late 1916 by David Lloyd George.

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon, Bt KG PC FZL DL (25 April 1862 – 7 September 1933), better known as Sir Edward Grey, Bt, was a British Liberal statesman. He served as Foreign Secretary from 1905 to 1916, the longest continuous tenure of any person in that office. He is probably best remembered for his remark at the outbreak of the First World War: "The lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our time". Ennobled as Viscount Grey of Fallodon in 1916, he was Ambassador to the United States between 1919 and 1920 and Leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Lords between 1923 and 1924.

And what was happening in London ?

|

| Herbert Henry Asquith |

Well Asquith had driven to Buckingham Palace early in the morning.

His intention, once he had got the King out of bed, was to ask the monarch to write to the Tsar, asking him to stop the mobilisation of the Russian forces.

|

| King-Emperor George V |

And why should George, still wearing his brown dressing gown, do this ?

Well, - Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, was George's first cousin (their mothers were sisters).

The letter itself had been written by Edward Grey, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, but it required the King's approval, and his handwritten prefix - 'Dear Nicky'.

Did it do any good ? .... No !

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, KG, KC, PC, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928) served as the Liberal Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1908 to 1916. As Prime Minister, he led his Liberal party to a series of domestic reforms, including social insurance and the reduction of the power of the House of Lords. He led the nation into the First World War, but a series of military and political crises led to his replacement in late 1916 by David Lloyd George.

|

| Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon |

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon, Bt KG PC FZL DL (25 April 1862 – 7 September 1933), better known as Sir Edward Grey, Bt, was a British Liberal statesman. He served as Foreign Secretary from 1905 to 1916, the longest continuous tenure of any person in that office. He is probably best remembered for his remark at the outbreak of the First World War: "The lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our time". Ennobled as Viscount Grey of Fallodon in 1916, he was Ambassador to the United States between 1919 and 1920 and Leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Lords between 1923 and 1924.

The Second of August

1914

On 24 July 1914 the Belgian government had announced that if war came it would uphold its neutrality.

|

| Kingdom of Belgium © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

Explaining that an imminent French attack on Germany was expected, the German ultimatum demanded - 'with the greatest regret' - free passage for its troops through Belgium.

This was an essential precondition to the successful implementation of the Schlieffen Plan (see above).

Guarantees were also given for the safety and good treatment of the Belgian people and Belgian property.

Despite the polite tone of the request, Germany felt impelled to warn the Belgian government that failure to comply would automatically bring Belgium into military conflict with Germany.

Germany was justified in suggesting to the Belgian Government that there would be an imminent French attack as, on the 2nd of August 1914 France mobilized its forces and sent them to the German border.

|

| Grand-Duchy of Luxemburg © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

In response, Germany crossed the borders of the Grand-Duchy of Luxemburg, which was an important step in the execution of the Schlieffen Plan.

King Albert, King of the Belgians, however, in council, explained to his ministers that the German requests were a breach of Belgium’s neutrality and independence, and that it was time for the Belgians to defend themselves from Germany.

The ministers, in a vast majority, agreed.

The Belgian reaction, however, helped the public opinion in Germany to believe they were in a defensive war.

And now we move east.

Far beyond Central Europe (Mitteleuropa), the Ottoman – German Alliance was ratified on August 2, 1914.

The alliance was created as part of a joint-cooperative effort that would strengthen and modernize the ailing Ottoman military, as well as possibly providing Germany safe passage into neighbouring British colonies.

On the eve of the First World War, the Ottoman Empire was in ruinous shape.

As a result of subsequent wars fought in this period, territories were lost, the economy was in shambles, and people were demoralized and tired.

What the Empire needed was time to recover and to carry out reforms; however, there was no time, because the world was sliding into war.

For reasons best known to the Ottomans, staying neutral and focusing on recovery did not appear to be possible, the Empire had to ally with one or the other camp, because, after the Italo-Turkish War and Balkan Wars, it was completely out of resources.

There were not adequate quantities of weaponry and machinery left; and neither did the Empire have the financial means to purchase new ones.

The only option for the 'Sublime Port' (Ottoman Government) was to establish an alliance with a European power; and at first it did not really matter which one that would be.

As Talat Paşa, the Minister of Interior, wrote in his memoirs: “Turkey needed to join one of the country groups so that it could organize its domestic administration, strengthen and maintain its commerce and industry, expand its railroads, in short to survive and to preserve its existence.”

Mehmed Talaat Pasha (Turkish: 1874 – 15 March 1921), commonly known as Talaat Pasha, was one of the triumvirate known as the Three Pashas that de facto ruled the Ottoman Empire during the First World War.

The problem was that most European powers were not keen to conclude an alliance with the ailing Ottoman Empire.

Only Russia seemed to have an interest – however, under conditions that would have amounted a Russian protectorate on the Ottoman lands.

It was impossible to reconcile an alliance with the French: as France's main ally was Russia, the long-time enemy of the Ottoman Empire since the War of 1828.

Great Britain declined an Ottoman request.

The Ottoman Sultan Mehmed V specifically wanted the Empire to remain a non-belligerent nation, however pressure from some of Mehmed's senior advisors led the Empire to align with the Central Powers.

Mehmed V Reshad (Mehmed V Reşad or Reşat Mehmet) (2/3 November 1844 – 3/4 July 1918) was the 35th Ottoman Sultan. He was the son of Sultan Abdülmecid I. He was succeeded by his half-brother Mehmed VI.

Mehmed V hosted Kaiser Wilhelm II, his World War I ally, in Constantinople on 15 October 1917. He was made Generalfeldmarschall of the Kingdom of Prussia on 27 January 1916, and of the Empire of Germany on 1 February 1916.

Whilst Great Britain was unenthusiastic about aligning with the Ottoman Empire Germany was enthusiastic.

Germany needed the Ottoman Empire on its side.

The Orient Express had run directly to Constantinople since 1889, and prior to the First World War the Sultan had consented to a plan to extend it through Anatolia to Baghdad under German auspices.

This would strengthen the Ottoman Empire's link with industrialised Europe, while also giving Germany easier access to its African colonies and to trade markets in India.

To keep the Ottoman Empire from joining the Triple Entente, Germany encouraged Romania and Bulgaria to enter the Central Powers.

A secret treaty was concluded between the Ottoman Empire and the German Empire on August 2, 1914.

The Ottoman Empire was to enter the war on the side of the Central Powers one day after the German Empire declared war on Russia.

The alliance was ratified on 2 August by many high ranking Ottoman officials, including Grand Vizier Said Halim Paşa, the Minister of War Enver Paşa, the Interior Minister Talat Paşa, and Head of Parliament Halil Bey.

Said Halim Pasha (Albanian: 18 January 1865 – 5 December 1921) was a statesman who served as the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire from 1913 to 1917. Born in Cairo, Egypt, he was the grandson of Muhammad Ali of Egypt, often considered the founder of modern Egypt. He was one of the signers in Ottoman–German Alliance. Yet, he resigned after the incident of the pursuit of Goeben and Breslau, an event which served to cement the Ottoman–German alliance during World War I. It is claimed that Mehmed V wanted a person in whom he trusted as Grand Vizier, and that he asked Said Halim to stay in his post as long as possible. Said Halim's term lasted until 1917, cut short because of continuous clashes between him and the Committee of Union and Progress, which by then controlled the Imperial Government of the Ottoman Empire.

Ismail Enver Pasha (Turkish: 22 November 1881 – 4 August 1922), commonly known as Enver Pasha, was an Ottoman military officer and a leader of the 1908 Young Turk Revolution. He was the main leader of the Ottoman Empire in both Balkan Wars and World War I. Throughout his career, he was known by increasingly elevated titles as he rose through military ranks, including Enver Efendi (انور افندي), Enver Bey (انور بك), and finally Enver Pasha, "Pasha" being the epithet Ottoman military officers gained after they were promoted to the rank of Mirliva.

However, there was no signature from the House of Osman (?) as the Sultan Mehmed V did not sign it.

The Sultan was the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, as written in the constitution, this made the legitimacy of the Alliance questionable.

This meant that the army was not be able to fight on behalf of the Sultan.

The Sultan himself had wanted the Empire to remain neutral.

He did not wish to command a war himself, and as such left the Cabinet to do much of his bidding.

The third member of the cabinet of the Three Pashas, Djemal Pasha, also did not sign the treaty as he had tried, unsuccessfully, to form an alliance with France.

Ahmed Cemal Pasha (Turkish: May 1872 – 21 July 1922), commonly know as Djemal Pasha, was an Ottoman military leader and one-third of the military triumvirate known as the Three Pashas that ruled the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Djemal was also Mayor of Istanbul.

The Alliance therefore was not universally accepted by all parts of the Ottoman government

The Ottoman Empire itself did not enter the war until German elements in the Ottoman Navy took matters into their own hands and bombarded Russian ports on the 29th of October 1914.

The ministers, in a vast majority, agreed.

The Belgian reaction, however, helped the public opinion in Germany to believe they were in a defensive war.

And now we move east.

Far beyond Central Europe (Mitteleuropa), the Ottoman – German Alliance was ratified on August 2, 1914.

The alliance was created as part of a joint-cooperative effort that would strengthen and modernize the ailing Ottoman military, as well as possibly providing Germany safe passage into neighbouring British colonies.

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

As a result of subsequent wars fought in this period, territories were lost, the economy was in shambles, and people were demoralized and tired.

What the Empire needed was time to recover and to carry out reforms; however, there was no time, because the world was sliding into war.

For reasons best known to the Ottomans, staying neutral and focusing on recovery did not appear to be possible, the Empire had to ally with one or the other camp, because, after the Italo-Turkish War and Balkan Wars, it was completely out of resources.

There were not adequate quantities of weaponry and machinery left; and neither did the Empire have the financial means to purchase new ones.

|

As Talat Paşa, the Minister of Interior, wrote in his memoirs: “Turkey needed to join one of the country groups so that it could organize its domestic administration, strengthen and maintain its commerce and industry, expand its railroads, in short to survive and to preserve its existence.”

Mehmed Talaat Pasha (Turkish: 1874 – 15 March 1921), commonly known as Talaat Pasha, was one of the triumvirate known as the Three Pashas that de facto ruled the Ottoman Empire during the First World War.

The problem was that most European powers were not keen to conclude an alliance with the ailing Ottoman Empire.

Only Russia seemed to have an interest – however, under conditions that would have amounted a Russian protectorate on the Ottoman lands.

It was impossible to reconcile an alliance with the French: as France's main ally was Russia, the long-time enemy of the Ottoman Empire since the War of 1828.

Great Britain declined an Ottoman request.

|

محمد خامس

Ottoman Sultan Mehmed V |

Mehmed V Reshad (Mehmed V Reşad or Reşat Mehmet) (2/3 November 1844 – 3/4 July 1918) was the 35th Ottoman Sultan. He was the son of Sultan Abdülmecid I. He was succeeded by his half-brother Mehmed VI.

Mehmed V hosted Kaiser Wilhelm II, his World War I ally, in Constantinople on 15 October 1917. He was made Generalfeldmarschall of the Kingdom of Prussia on 27 January 1916, and of the Empire of Germany on 1 February 1916.

Whilst Great Britain was unenthusiastic about aligning with the Ottoman Empire Germany was enthusiastic.

Germany needed the Ottoman Empire on its side.

The Orient Express had run directly to Constantinople since 1889, and prior to the First World War the Sultan had consented to a plan to extend it through Anatolia to Baghdad under German auspices.

This would strengthen the Ottoman Empire's link with industrialised Europe, while also giving Germany easier access to its African colonies and to trade markets in India.

To keep the Ottoman Empire from joining the Triple Entente, Germany encouraged Romania and Bulgaria to enter the Central Powers.

|

سعيد حليم پاشا

Said Halim Paşa

|

The Ottoman Empire was to enter the war on the side of the Central Powers one day after the German Empire declared war on Russia.

The alliance was ratified on 2 August by many high ranking Ottoman officials, including Grand Vizier Said Halim Paşa, the Minister of War Enver Paşa, the Interior Minister Talat Paşa, and Head of Parliament Halil Bey.

Said Halim Pasha (Albanian: 18 January 1865 – 5 December 1921) was a statesman who served as the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire from 1913 to 1917. Born in Cairo, Egypt, he was the grandson of Muhammad Ali of Egypt, often considered the founder of modern Egypt. He was one of the signers in Ottoman–German Alliance. Yet, he resigned after the incident of the pursuit of Goeben and Breslau, an event which served to cement the Ottoman–German alliance during World War I. It is claimed that Mehmed V wanted a person in whom he trusted as Grand Vizier, and that he asked Said Halim to stay in his post as long as possible. Said Halim's term lasted until 1917, cut short because of continuous clashes between him and the Committee of Union and Progress, which by then controlled the Imperial Government of the Ottoman Empire.

Ismail Enver Pasha (Turkish: 22 November 1881 – 4 August 1922), commonly known as Enver Pasha, was an Ottoman military officer and a leader of the 1908 Young Turk Revolution. He was the main leader of the Ottoman Empire in both Balkan Wars and World War I. Throughout his career, he was known by increasingly elevated titles as he rose through military ranks, including Enver Efendi (انور افندي), Enver Bey (انور بك), and finally Enver Pasha, "Pasha" being the epithet Ottoman military officers gained after they were promoted to the rank of Mirliva.

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

However, there was no signature from the House of Osman (?) as the Sultan Mehmed V did not sign it.

The Sultan was the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, as written in the constitution, this made the legitimacy of the Alliance questionable.

This meant that the army was not be able to fight on behalf of the Sultan.

The Sultan himself had wanted the Empire to remain neutral.

He did not wish to command a war himself, and as such left the Cabinet to do much of his bidding.

|

| احمد جمال پاشا Ahmed Cemal Pasha |

Ahmed Cemal Pasha (Turkish: May 1872 – 21 July 1922), commonly know as Djemal Pasha, was an Ottoman military leader and one-third of the military triumvirate known as the Three Pashas that ruled the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Djemal was also Mayor of Istanbul.

The Alliance therefore was not universally accepted by all parts of the Ottoman government

The Ottoman Empire itself did not enter the war until German elements in the Ottoman Navy took matters into their own hands and bombarded Russian ports on the 29th of October 1914.

The Third of August

1914

|

| Sir Edward Grey |

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

It is information I have received from the Belgian Legation in London, and is to the following effect:

"Germany sent yesterday evening at seven o'clock a note proposing to Belgium friendly neutrality, covering free passage on Belgian territory, and promising maintenance of independence of the kingdom and possession at the conclusion of peace, and threatening, in case of refusal, to treat Belgium as an enemy. A time-limit of twelve hours was fixed for the reply. The Belgians have answered that an attack on their neutrality would be a flagrant violation of the rights of nations, and that to accept the German proposal would be to sacrifice the honour of a nation. Conscious of its duty, Belgium is finally resolved to repel aggression by all possible means."

Of course, I can only say that the Government are prepared to take into grave consideration the information which they have received. I make no further comment upon it.'

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

In the afternoon, two days after declaring war on Russia, Germany declared war on France, moving ahead with a long-held strategy, conceived by the former chief of staff of the German army, Alfred von Schlieffen, for a two-front war against France and Russia.

Presented by the German Ambassador to Paris:

M. Le President, the German administrative and military authorities have established a certain number of flagrantly hostile acts committed on German territory by French military aviators. Several of these have openly violated the neutrality of Belgium by flying over the territory of that country; one has attempted to destroy buildings near Wesel; others have been seen in the district of the Eifel; one has thrown bombs on the railway near Carlsruhe and Nuremberg. I am instructed, and I have the honour to inform your Excellency, that in the presence of these acts of aggression the German Empire considers itself in a state of war with France in consequence of the acts of this latter Power.

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

My diplomatic mission having thus come to an end, it only remains for me to request your Excellency to be good enough to furnish me with my passports, and to take the steps you consider suitable to assure my return to Germany, with the staff of the Embassy, as well as, with the Staff of the Bavarian Legation and of the German Consulate General in Paris.

Hours later, France made its own declaration of war against Germany, readying its troops to move into the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, which it had forfeited to Germany in the settlement that ended the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.

With Germany officially at war with France and Russia, a conflict originally centred in the Balkans - with the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife by a Serbian nationalist, in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, and a subsequent stand-off between Austria-Hungary, Serbia and Serbia’s powerful Slavic supporter, Russia - had erupted into a full-scale European war.

|

| Schlieffen Plan - Open in new tab to view full size |

This threat to Belgium, whose neutrality had been guaranteed by a treaty concluded by a number of European powers - including Britain, France and Germany - in 1839, united a divided British government in opposition against Germany.

That August, as the great powers of Europe readied their armies and navies for war, no one was preparing for a long struggle - all the participants were counting on a short, decisive conflict that would end in their favour.

|

| Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener |

|

| Kaiser Wilhelm II |

Even though some military leaders, including German Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke, and his French counterpart, Joseph Joffre, foresaw a longer conflict, they foolishly did not modify their war strategy to prepare for that eventuality.

One man, the controversial new war secretary in Britain, Lord Horatio Kitchener, did act on his conviction that the war would be a lasting one, insisting from the beginning of the war - against considerable opposition - on the need to build up Britain’s armed forces.

"A nation like Germany," Kitchener argued, "after having forced the issue, will only give in after it is beaten to the ground. This will take a very long time. No one living knows how long."

Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, KG, KP, GCB, OM, GCSI, GCMG, GCIE, ADC, PC - (24 June 1850 – 5 June 1916) was a senior British Army officer and colonial administrator who won fame for his imperial campaigns and later played a central role in the early part of the First World War, although he died halfway through it. Kitchener won fame in 1898 for winning the Battle of Omdurman and securing control of the Sudan, after which he was given the title "Lord Kitchener of Khartoum"; as Chief of Staff (1900–02) in the Second Boer War he played a key role in Lord Roberts' conquest of the Boer Republics, then succeeded Roberts as commander-in-chief. His term as Commander-in-Chief (1902–09) of the Army in India saw him quarrel with another eminent proconsul, the Viceroy Lord Curzon, who eventually resigned. Kitchener then returned to Egypt as Sirdar and Consul-General. In 1914, at the start of the First World War, Lord Kitchener became Secretary of State for War, a Cabinet Minister. One of the few to foresee a long war, he organised the largest volunteer army that Britain, and indeed the world, had seen and a significant expansion of materials production to fight Germany on the Western Front

The Fourth of August

1914

And now, for England, the peace had ended...

And now, for England, the peace had ended...

PEACE

|

| © Copyright Peter Crawford 2014 |

Now, God be thanked Who has matched us with His hour,

And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping,

With hand made sure, clear eye, and sharpened power,

To turn, as swimmers into cleanness leaping,

Glad from a world grown old and cold and weary,

Leave the sick hearts that honour could not move,

And half-men, and their dirty songs and dreary,

And all the little emptiness of love !

Oh ! we, who have known shame, we have found release there,

Where there's no ill, no grief, but sleep has mending,

Naught broken save this body, lost but breath;

Nothing to shake the laughing heart's long peace there

But only agony, and that has ending;

And the worst friend and enemy is but Death.

|

| Granchester |

| Rupert Brooke's Grave - Skyros |

Endure, O Earth! and thou, awaken,

Purged by this dreadful winnowing—fan,

O wronged, untameable, unshaken

Soul of divinely suffering man.

Robert Laurence Binyon, CH (10 August 1869 – 10 March 1943) was an English poet, dramatist and art scholar. His most famous work, 'For the Fallen', is well known for being used in Remembrance Sunday services. Three of Binyon's poems, including "For the Fallen", were set by Sir Edward Elgar in his last major orchestra/choral work, the superb "Spirit of England".

And so we are left with the question: why did England declare war on Germany on 4th August 1914 ?

And we may well ask the question, would Belgium or France have declared war on Germany if Germany had invaded England in 1914 ?

Many elements in the English establishment undoubtedly wanted war with the German Empire and the Ottoman Empire, in order to thwart the building of the Berlin to Baghdad railway, and thereby protect its access to the Indian Empire.

Equally they feared Germany hegemony on the continent.

In the years prior to the declaration of war a fear of German militarism replaced a previous admiration for German culture and literature.

At the same time, journalists produced a stream of articles on the threat posed by Germany.

Alfred Harmsworth had commissioned author William Le Queux to write the best-sellingn novel 'The Invasion of 1910', which originally appeared in serial form in the 'Daily Mail' in 1906, and has been referred to by historians as inducing an atmosphere of paranoia, mass hysteria and

And so the Germans became 'the Hun', and one of Europe's greatest cultures became - for the English at least:

Now previous European wars in the Nineteenth century, like the Franco-Prussian War (Deutsch-Französischer Krieg), the Wars of Italian Unification, and the Austro-Prussian War, to name a few, had been relatively short affairs, with fairly small causalities, and most people though that the war that began in 1914 would be similar, with fluid movements of infantry and cavalry, culminating in a fairly decisive defeat for one side or the other.

What no one expected was the development of 'trench warfare' and the use of huge conscript armies and massed artillery.

And so the supposedly civilised, intelligent countries of Europe stumbled blindly into the greatest military disaster the world had ever seen - cheering enthusiastically all the way.

Now it is not the intention of this blog to chart, in detail the history of the Great War, but rather to highlight the effect that the war had on the people of England.

And we may well ask the question, would Belgium or France have declared war on Germany if Germany had invaded England in 1914 ?

Many elements in the English establishment undoubtedly wanted war with the German Empire and the Ottoman Empire, in order to thwart the building of the Berlin to Baghdad railway, and thereby protect its access to the Indian Empire.

Equally they feared Germany hegemony on the continent.

In the years prior to the declaration of war a fear of German militarism replaced a previous admiration for German culture and literature.

|

| 'The Invasion of 1910' |

Alfred Harmsworth had commissioned author William Le Queux to write the best-sellingn novel 'The Invasion of 1910', which originally appeared in serial form in the 'Daily Mail' in 1906, and has been referred to by historians as inducing an atmosphere of paranoia, mass hysteria and

|

| Anti German Riots |

With the declaration of war, anti-German feeling led to rioting, assaults on suspected Germans and the looting of stores owned by people with German-sounding names.

Increasing anti-German hysteria even threw suspicion upon the English monarchy, and King George V was persuaded to change his German name of Saxe-Coburg und Gotha to 'Windsor', and relinquish all German titles and styles on behalf of those of his relatives who were British subjects.

Also in the England, the German Shepherd breed of dog was renamed to the euphemistic "Alsatian".

THE RAPE OF BELGIUM

If England had been completely justified in declaring war on the German Empire, it undoubtedly would not have felt it necessary to mount a vigorous propaganda campaign centred on the concept of the 'Rape of Belgium'.

|

| The Rape of Belgium |

The invasion of Belgium, with its very real suffering, was nevertheless represented in a highly stylized way that dwelt on perverse sexual acts, lurid mutilations, and graphic accounts of child abuse of dubious veracity.

In England, many patriotic publicists propagated these stories on their own.

For example popular writer William Le Queux described the German army as "one vast gang of Jack-the-Rippers", and described in graphic detail events such as a governess hanged naked and mutilated, the bayoneting of a small baby, or the "screams of dying women", raped and "horribly mutilated" by German soldiers, accusing them of cutting off the hands, feet, or breasts of their victims.

English propagandists were eager to move as quickly as possible from an explanation of the war that focused on the murder of an Austrian Archduke and his wife by Serbian nationalists to the question of the invasion of neutral Belgium.

+-+1914+-++Der+Grosse+Krieg+-+Deutschland+und+der+Erste+Weltkrieg+-+Deutschland+Ostmark+-+Peter+Crawford.jpg) |

| Kaiserlich Deutsche Ulanen |

|

| 'Thrown to the Swine' Louis Raemaekers |

Although the infamous German phrase "scrap of paper" (referring to the 1839 Treaty of London) galvanized a large segment of English intellectuals in support of the war, in more proletarian circles, (that is normal circles) this imagery had far less impact.

For example, Labour politician Ramsay MacDonald upon hearing about it, declared that "Never did we arm our people and ask them to give up their lives for a less good cause than this".

As the German advance in Belgium progressed, English newspapers started to publish stories on German atrocities.

|

| The Angels of Mons |

|

| The Crucified Soldier |

The English press, "quality" and tabloid alike, showed less interest in the "inventory of stolen property and requisitioned goods" that constituted the bulk of the official Belgian Reports.

Instead, accounts of rape and bizarre mutilations flooded the British press.

The intellectual discourse on the "scrap of paper" was then mixed with the more graphic imagery depicting Belgium as a brutalized woman, exemplified by the cartoons of Louis Raemaekers.

The English government regularly fabricated bizarre stories, and supplied them to the public, such as Belgian nuns being tied to the clappers of church bells and crushed to death when the bells were rung.

Reports paved the way for other war propaganda such as 'The Crucified Soldier', 'The Angels of Mons', and the 'Kadaververwertungsanstalt'.

And so the Germans became 'the Hun', and one of Europe's greatest cultures became - for the English at least:

'the force that feeds desire on

Dreams of a prey to seize and kill,

The barren creed of blood and iron,

Vampire of Europe's wasted will…'

'To me those hours seemed like a release from the painful feelings of my youth.

Even today I am not ashamed to say that, overpowered by stormy enthusiasm, I fell down on my knees and thanked Heaven from an overflowing heart for granting me the good fortune of being permitted to live at this time.

|

| World War I Iron Cross |

The reference here to 'iron', although Binyon may well have not known it, related to the production of iron jewellery between 1813 and 1815, when the Prussian royal family urged all citizens to contribute their gold and silver jewellery towards funding the uprising against Napoleon during the 'German War of Liberation'.

In return the people were given iron jewellery such as brooches and finger rings, often with the inscription 'Gold gab ich für Eisen' (I gave gold for iron), or 'Für das Wohl des Vaterlands' (For the welfare of our country / fatherland), or with a portrait of Frederick William III of Prussia on the back - and hence the Iron Cross - and it should be noted that Napoleon was not only an enemy of Germany, but also of England.

And it should be remembered that France, England's main ally in the Great War, actually wanted war with the German Empire, in a pathetic attempt to wipe out the humiliation it had experienced in the Franco-Prussian War (Deutsch-Französischer Krieg) - (19 July 1870 – 10 May 1871).

And so the stage was set for the conflict.

OVER BY CHRISTMAS

|

| French Cavalry in Paris leaving for the Front |

|

| German Infantry leaving for the Front |

Now Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany had told his troops, - "You will be home before the leaves have fallen from the trees,".

And in the rest of Europe most people were confident that the war would be over by Christmas - that is Christmas 1914.

What now seems strange is that in all the belligerent countries most people welcomed the war.

This is what Adolf Hitler had to say about the declaration of war:

|

| Adolf Hitler - der soldat |

|

| Adolf Hitler Berlin 1914 |

Even today I am not ashamed to say that, overpowered by stormy enthusiasm, I fell down on my knees and thanked Heaven from an overflowing heart for granting me the good fortune of being permitted to live at this time.

A fight for freedom had begun, mightier than the earth had ever seen; for once Destiny had begun its course, the conviction dawned on even the broad masses that this time not the fate of Serbia or Austria was involved, but whether the German nation was to be or not to be.

For the last time in many years the people had a prophetic vision of its own future.

Thus, right at the beginning of the gigantic struggle the necessary grave undertone entered into the ecstasy- of an overflowing enthusiasm; for this knowledge alone made the national uprising more than a mere blaze of straw.'

|

| German Troops Mobilising - 1914 |

Now previous European wars in the Nineteenth century, like the Franco-Prussian War (Deutsch-Französischer Krieg), the Wars of Italian Unification, and the Austro-Prussian War, to name a few, had been relatively short affairs, with fairly small causalities, and most people though that the war that began in 1914 would be similar, with fluid movements of infantry and cavalry, culminating in a fairly decisive defeat for one side or the other.

What no one expected was the development of 'trench warfare' and the use of huge conscript armies and massed artillery.

And so the supposedly civilised, intelligent countries of Europe stumbled blindly into the greatest military disaster the world had ever seen - cheering enthusiastically all the way.

Now it is not the intention of this blog to chart, in detail the history of the Great War, but rather to highlight the effect that the war had on the people of England.

to be continued